Opportunities for making the trade safe and environmentally sound, while still keeping it profitable

Like many waste streams in Nigeria, the ULAB waste stream has the potential to contribute to being a source of growth and employment. In the case of ULAB in particular, the value chain is well organised and can be capitalised upon. On the other hand, ULABs are one of the most critical waste streams in terms of potential negative health and safety impacts. Any mismanagement in the recycling chain will almost certainly lead to severe and long lasting contamination of the environment and adverse impacts on human health.

Nigeria already has one well equipped secondary lead smelter. International research indicates that such facilities are rare in African countries and therefore Nigeria has an advantage in this regard and that it may even be well positioned to become a hub for sound ULAB recycling in West Africa. This local smelter/battery manufacturer faces however significant competition from imports and local low-standard smelters, and in the sourcing of ULAB at convenient prices, as international lead traders can pay higher prices for ULAB. It runs at a fraction of its full capacity. As a result the facility does not work at full capacity and its long-term viability is at risk, with resultant loss of employment.

Enforcement is key to the success of sound ULAB recycling in Nigeria. Clean industrial lead smelters are only profitable in strong regulatory environments. Lead smelters that do not respect environmental standards have lower costs for the same output as clean smelters. Therefore, clean lead smelters cannot compete in places where illegal and sub-standard industrial smelters are allowed to operate. NESREA is the responsible authority to audit facilities, make recommendations and ultimately to sanction non-performers, as a way of ensuring that Nigerian-based good performers have a level playing field. Failing to sanction non-performers is a disincentive to responsible investments in this sector.

Awareness raising and training are low-hanging fruits in the path to stronger enforcement. Lead blood tests of smelter workers and neighbouring communities, information on health impacts and awareness raising should go hand in hand. International experience (through one recent case in Kenya) shows that low-standard smelters were closed down after awareness on its health impacts spread amongst communities and authorities. Training of recyclers should be coupled with the development of roadmaps for facility improvement.

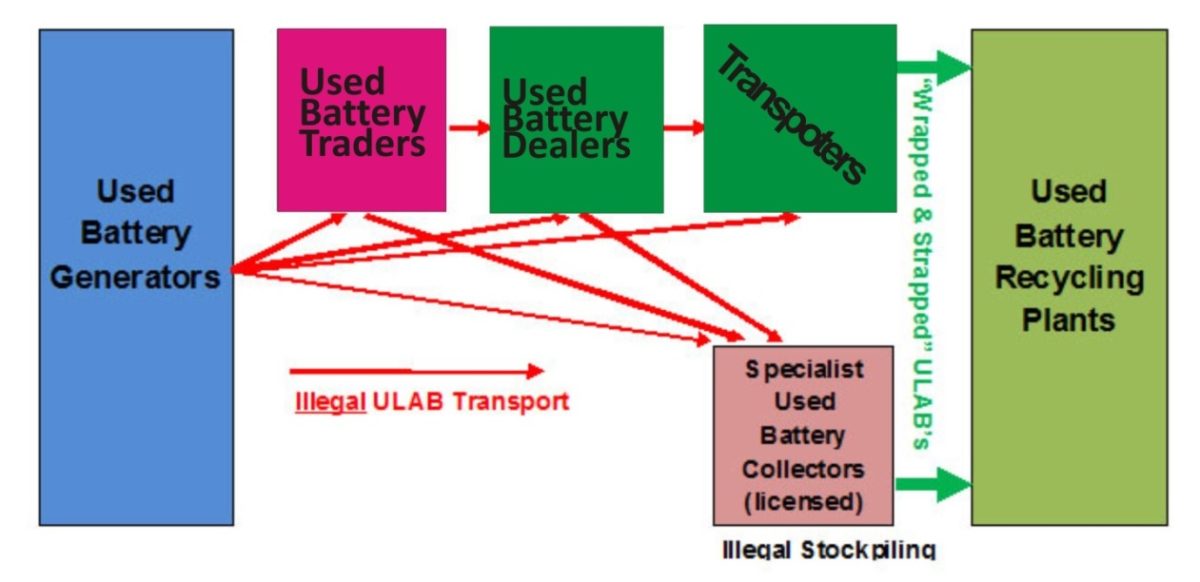

A further low-hanging opportunity exists for raising health and safety standards and awareness in the transport of large “wrapped and strapped” ULAB volumes[1]. Similar opportunities exist for collection and storage practices.

The option of exporting complete batteries for sound recycling abroad should be considered only if sufficient sound domestic recycling capacities are not available. The Federal Ministry of Environment has the responsibility to issue export permits and notifications required in the context of the Basel Convention, and as such would be the best positioned governmental body to facilitate export to responsible recyclers abroad.

A ULAB-related resolution has been approved in the United Nations Environment Assembly, with prospects of leading to international standards could save Nigeria considerable resources in developing its own guidelines [2]. In the meantime, activities on standards should be guided by the Technical Guidelines for the Environmentally Sound Management of Waste Lead-acid Batteries [3]

Lessons can be drawn from the efforts taking place in the e-waste sector in the field of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). If properly implemented, EPR can help to internalise the health and environmental costs of ULAB. EPR encourages producers and importers to take the product’s life cycle from cradle-to-cradle into perspective, by making them responsible for the take-back, recycling and final disposal of the product.

The implementation of the EPR programme for e-waste has faced considerable hurdles in terms of lack of stakeholder commitment and data confidentiality. The experience has shown that the best approach is to start with a sub-set of relevant stakeholders to foster ownership of the programme and enhance commitment.

In the long term, a “battery PRO” (Producer Responsibility Organisation) could work to improve collection and recycling of ULAB in Nigeria, and support the dialogue with the informal ULAB collection and recycling sector. There are significant differences between ULAB and e-waste. While e-waste recycling is most profitable in informal backyard processes that are extremely difficult to be regulated and controlled (if regulated, recyclers usually just move to other places), ULAB recycling is most profitable in industrial smelters of medium or large scale. Therefore, ULAB recycling is much more centralised and tied to capital intensive equipment. Such facilities are few in numbers and can be audited and controlled without creating the risk of pushing the industry into uncontrollable backyards.

Like Electrical and Electronic Equipment (EEE), a considerable portion of LABs sold in the Nigerian market are imported. The first point of control for an EPR programme should therefore be at the border. The “Product Take-Back” implementation instrument adopted by the e-waste sector would also be appropriate for the ULAB sector, supplemented with the Advanced Recycling Fees (ARF) at the point of product entry.

Like the e-waste sector, it would also be advantageous to start with a pilot phase. An implementation model should be developed for a specified period, followed by an evaluation.